Exploring the Landscape of Convolutional Neural Networks

Objective :

- Fundamentals of CNN

- Understanding the Evolution of CNN Architectures

- Practical Applications

Table of Contents

- Fundamentals of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

- Evolution of CNN Architectures

- Practical Applications of CNN Architectures

- References

- Conclusion

1. Fundamentals of Convolutional Neural Networks(CNN)

At their core, CNNs leverage a series of convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers to process input data. The convolutional layers apply learnable filters to input images, extracting features such as edges, textures, and patterns. Pooling layers then downsample the feature maps, reducing their spatial dimensions while preserving important features. Finally, fully connected layers combine these features to make predictions about the input data.

A key difference between Dense layer and a Convolutional layer is that, dense layer learns global patterns whereas convolutional layer learns local patterns. This key distinction allows convolutional layers to capture spatial hierarchies and learn translational invariance.

Translational Invariance:

A CNN can learn to detect patterns regardless of their position within the input image. For example, a CNN trained to recognize cats should be able to identify a cat regardless of whether it appears in the center or the corner of the image. Translational invariance is a desirable property in tasks such as object recognition and classification, as it allows models to generalize better to unseen data and variations in object position or orientation

Spatial Hierarchy:

At the lowest layers of a CNN, simple features such as edges, corners, and textures are learned. These features have a small spatial scope and represent basic visual elements present in the input data. As we move deeper into the network, features become more complex and encompass larger spatial regions. For example, a deeper layer might learn features like shapes, object parts, or entire objects.

The basic components of a CNN architecture are:

- Convolutional Layer

- Pooling Layer

- Activation Function

- Batch Normalization

- Dropout

- Fully Connected Layer

Convolutional Layer

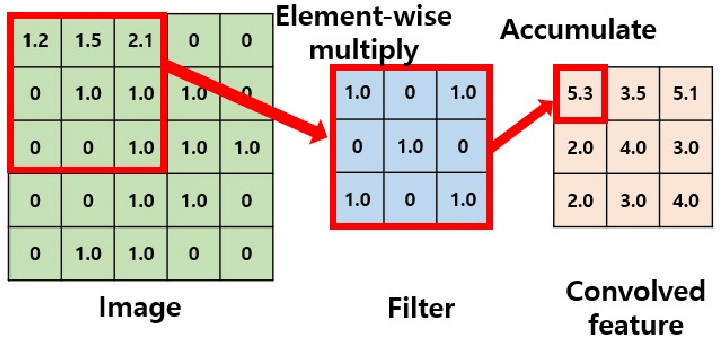

A convolutional layer in a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) performs feature extraction by applying a set of learnable filters (kernels) to the input data. Each filter scans across the input data, computing the dot product between its weights and the values in its receptive field, resulting in a feature map that highlights the presence of certain patterns or features in the input.

Key aspects of a convolutional layer: </br>

Feature Detection: The convolutional filters detect various features such as edges, textures, and shapes present in the input data.

Spatial Hierarchies: Through the hierarchy of layers, convolutional layers capture increasingly complex and abstract spatial structures, building upon features learned in previous layers.

Parameter Sharing: By sharing weights across different spatial locations, convolutional layers learn translational invariance, enabling them to detect patterns regardless of their position within the input.

Pooling Layer

Pooling layers reduce the spatial dimensions of feature maps, making the model more computationally efficient while retaining the most important information. Pooling also helps to make CNNs more robust to small translations in the input.

The two most common types of pooling are:

-

Max Pooling: This method takes the maximum value from a set of values in a small window of the feature map. Max pooling focuses on the most prominent features and is widely used in image-based tasks.

Example: If the window contains values

[1, 3, 2, 8], max pooling will output8. -

Average Pooling: It computes the average of the values in a window, which smooths out the feature maps and is often used for downscaling.

Example: For the same window

[1, 3, 2, 8], average pooling outputs(1+3+2+8)/4 = 3.5.

Why Pooling? Pooling helps reduce the dimensionality of feature maps and ensures that only the essential features are preserved. This makes the network faster and less prone to overfitting.

Activation Functions

Activation functions introduce non-linearity into neural networks, which is critical for learning complex patterns and making accurate predictions. CNNs rely on a few key activation functions:

-

ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): The most popular activation function in CNNs. It simply returns the input if it’s positive and returns zero if it’s negative.

Example: For an input of

[-2, 0, 3], ReLU outputs[0, 0, 3].Why ReLU? ReLU solves the vanishing gradient problem that plagued earlier activation functions (like Sigmoid), allowing for faster and more efficient training.

-

Leaky ReLU: A variation of ReLU that allows a small gradient even for negative inputs. This avoids the problem of dead neurons (neurons that never activate).

-

Sigmoid: This function squashes the input into a range between 0 and 1, making it ideal for binary classification. However, it tends to suffer from vanishing gradients in deep networks.

-

Tanh: Similar to Sigmoid but squashes the input between -1 and 1. While it solves the zero-centered problem of Sigmoid, it still suffers from vanishing gradients.

Batch Normalization

Batch Normalization (BatchNorm) is a technique that normalizes the inputs to each layer in the network, helping to stabilize and accelerate the training process. By normalizing the activations, BatchNorm ensures that each layer receives inputs with a consistent distribution, which makes training deep networks much more efficient.

Benefits of BatchNorm:

- Faster Convergence: Normalizing the inputs allows for higher learning rates, which speeds up the convergence of the model.

- Reduced Sensitivity to Initialization: Models are less sensitive to the initial weight values, making the training process smoother.

- Regularization: It provides a slight regularization effect, similar to dropout, which helps prevent overfitting.

Dropout

Dropout is a regularization technique where, during training, a random subset of neurons in a layer is “dropped” (i.e., set to zero). This forces the network to learn more robust features and prevents over-reliance on specific neurons, which helps reduce overfitting.

How Dropout Works:

- During each training step, a fraction (e.g., 50%) of neurons is dropped randomly.

- During inference (when the model is making predictions), all neurons are used, but their activations are scaled down by the dropout rate to balance the network.

Why It Works: Dropout essentially simulates training many different networks simultaneously, which helps in learning generalized features.

Fully Connected Layer

The Fully Connected Layer (or Dense Layer) comes at the end of the CNN architecture, where all neurons are connected to every neuron in the previous layer. This is where the final decision-making happens. After the convolutional and pooling layers extract the spatial features, the fully connected layers use these features to predict the final class (in the case of classification tasks) or output value (in regression tasks).

Why Fully Connected Layers? While convolutional layers capture local features, the fully connected layer combines these features globally and applies them to the classification or regression problem.

2. Evolution of CNN Architectures: From LeNet to EfficientNet

The architecture of CNNs has evolved significantly over the years. Here’s a deeper look into how each architecture addressed the challenges faced by its predecessor:

2.1. LeNet-5 (1998): The Pioneer

LeNet-5, designed by Yann LeCun, is one of the first CNNs that made practical applications like digit recognition on the MNIST dataset possible. This architecture had two convolutional layers followed by two fully connected layers. Despite its simplicity, it achieved remarkable results for its time.

Flaws:

- Shallow Architecture: LeNet-5 has very few layers, which limited its ability to capture complex patterns in larger datasets.

- Overfitting: Small networks like LeNet-5 were prone to overfitting, especially when applied to more complex tasks with larger datasets.

What Came Next: As datasets grew, deeper architectures were needed to capture more abstract features and avoid overfitting.

2.2. AlexNet (2012): The Breakthrough

AlexNet, created by Alex Krizhevsky, made CNNs a household name after it won the 2012 ImageNet competition by a large margin. AlexNet was deeper and wider than LeNet-5, using five convolutional layers followed by three fully connected layers. The innovation came from using ReLU activations, dropout for regularization, and GPU acceleration for training large datasets.

Flaws:

- High Computational Cost: AlexNet introduced a deeper architecture, but it came at the cost of high computational requirements.

- Manual Design: There was a lot of manual tuning involved, such as deciding the number of layers, neurons, and filters.

How It Was Resolved: The rise of even deeper architectures called for strategies to reduce computation and make models more efficient.

2.3. VGGNet (2014): Deeper but Simpler

VGGNet, proposed by the Visual Geometry Group at Oxford, took CNN depth to the next level by stacking small 3x3 convolutional filters sequentially. The most popular models, VGG16 and VGG19, used 16 and 19 layers, respectively. By using smaller filters, VGGNet made the network simpler and more uniform, focusing on depth.

Flaws:

- Too Many Parameters: Despite the simplicity of the design, VGGNet has a huge number of parameters (138 million in VGG16!), making it resource-intensive.

- Slow Training: The large number of parameters slowed down training, requiring a lot of computational power and memory.

What Came Next: The need for efficient architectures that can achieve similar performance but with fewer parameters led to GoogLeNet and ResNet.

2.4. GoogLeNet (Inception, 2014): Smarter, Not Just Deeper

GoogLeNet introduced the Inception module, a game-changing concept where different types of convolutions (1x1, 3x3, and 5x5) were applied in parallel. This allowed the network to capture patterns at multiple scales, increasing both efficiency and accuracy. GoogLeNet used fewer parameters than VGGNet, thanks to global average pooling instead of fully connected layers.

Flaws:

- Complexity in Design: Although the Inception module was highly efficient, its design was more complex and not as intuitive as previous architectures.

- Manual Crafting of Inception Modules: Inception modules needed to be manually designed, which required a lot of expertise and fine-tuning.

How It Was Resolved: Residual connections in ResNet simplified the training of very deep networks, reducing the risk of manual design flaws.

2.5. ResNet (2015): Deeper Networks Without the Pain

ResNet solved the problem of “vanishing gradients” that plagued earlier deep networks. It introduced residual connections, or “skip connections,” allowing gradients to flow more easily through the network during backpropagation. This breakthrough made it possible to train networks with over 100 layers.

Flaws:

- Computational Expense: Despite solving the depth problem, ResNet is still computationally expensive.

- Redundant Layers: Not every layer in a deep ResNet necessarily contributes equally to learning, which can lead to redundancy.

What Came Next: While ResNet allowed for extreme depth, there was still a demand for architectures that could scale both depth and width efficiently—leading to EfficientNet.

2.6. EfficientNet (2019): Scaling Done Right

EfficientNet revolutionized the way we think about scaling architectures. Instead of increasing depth, width, or input resolution arbitrarily, EfficientNet used a compound scaling method to scale all dimensions uniformly. This balanced approach led to state-of-the-art performance while using fewer resources than previous models.

Flaws:

- Complex to Implement: EfficientNet requires careful compound scaling, which adds complexity in its design.

- Tuned for Specific Tasks: While highly efficient, EfficientNet might not always generalize well to tasks outside of image classification without modifications.

What It Resolved: EfficientNet provided a balance of depth, width, and resolution, making it the most efficient CNN architecture in terms of accuracy and computational cost.

3. Practical Applications of CNN Architectures

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been instrumental in solving real-world problems across various industries. Below, we explore the practical applications of the CNN architectures discussed earlier, with links to papers, websites, and working demos where possible.

3.1. LeNet-5 (1998)

Application: Handwritten digit recognition was the primary application of LeNet-5, which worked excellently on datasets like MNIST. It laid the groundwork for document digitization, postal address reading, and similar tasks.

- Paper: LeNet-5: Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition

- Demo: MNIST Handwritten Digit Recognition using LeNet-5

Use Case: Used in automated banking systems for reading checks and digitizing documents.

3.2. AlexNet (2012)

Application: AlexNet’s primary claim to fame was winning the 2012 ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC). It revolutionized image classification and object detection. AlexNet has been widely used in applications such as object detection in autonomous vehicles, facial recognition, and medical image classification.

- Paper: ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (AlexNet)

- Demo: AlexNet in PyTorch

Use Case: Powering computer vision applications like object detection in self-driving cars and facial recognition systems.

3.3. VGGNet (2014)

Application: VGGNet’s deep structure and smaller convolutional filters made it popular in image classification, especially in fine-grained tasks like facial recognition and medical imaging. VGG16 and VGG19 models are used in applications that require high accuracy.

- Paper: Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition (VGGNet)

- Demo: VGGNet for Image Classification

Use Case: Used for fine-grained image classification tasks, facial recognition, and deep learning-based anomaly detection in medical imaging.

3.4. GoogLeNet (Inception, 2014)

Application: GoogLeNet’s Inception module allows for efficient image classification, which has been used in applications such as video analysis, security surveillance, and large-scale object recognition systems. Its low parameter count makes it suitable for mobile devices and embedded systems.

Use Case: Used in video recognition systems, real-time surveillance systems, and for large-scale object recognition tasks.

3.5. ResNet (2015)

Application: ResNet is widely used in image classification, object detection, and semantic segmentation. Its use of residual connections allows for very deep networks, which makes it applicable in medical image analysis, autonomous vehicles, and high-end computer vision tasks.

Use Case: Used in advanced applications like medical diagnostics (e.g., detecting diseases from MRI scans), drone vision, and complex industrial inspection tasks.

3.6. EfficientNet (2019)

Application: EfficientNet has become the go-to architecture for real-time image processing tasks due to its balanced scaling of depth, width, and resolution. It is used in applications like mobile vision, automated agricultural systems (crop health monitoring), and in low-power, high-accuracy image recognition tasks.

- Paper: EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks

- Demo: EfficientNet in Keras

Use Case: Deployed in real-time image recognition on mobile devices, drones, and healthcare diagnostics with limited computational resources.

4. Conclusion

From simple digit recognition to powering sophisticated systems in healthcare, transportation, and entertainment, CNNs have proven to be remarkably versatile. The architectures discussed above, including LeNet-5, AlexNet, VGGNet, GoogLeNet, ResNet, and EfficientNet, have opened up endless possibilities for applying deep learning in practical, real-world scenarios. Whether you are working on a mobile application or deploying a large-scale object detection system, there’s a CNN architecture tailored for your needs.

5. References

-

LeNet-5: Yann LeCun, et al. “Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition.” Proceedings of the IEEE, 1998. LeNet Paper

-

AlexNet: Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey Hinton. “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks.” NIPS, 2012. AlexNet Paper

-

VGGNet: Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. “Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition.” arXiv, 2014. VGGNet Paper

-

GoogLeNet: Christian Szegedy, et al. “Going Deeper with Convolutions.” arXiv, 2014. GoogLeNet Paper

-

ResNet: Kaiming He, et al. “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition.” CVPR, 2015. ResNet Paper

-

EfficientNet: Mingxing Tan and Quoc V. Le. “EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks.” ICML, 2019. EfficientNet Paper